Seeing Reclusion in Ink Chrysanthemums

A late fragrance blooming with quiet self-possession

When spring flowers have long faded and summer has quieted down, the chrysanthemum finally opens—late, calm, unhurried. In Chinese, it’s often praised for its “late fragrance”: a lingering scent as the season turns, a calm that doesn’t need to announce itself. That’s why the chrysanthemum carries the spirit of yì (逸)— an unforced ease, a graceful step back from noise without losing oneself. It often appears in life’s closing chapters, when ambition softens into clarity. And in that story, one figure stands at the center: Tao Yuanming.

Tao Yuanming and the Beginning of Reclusion

If “success” has ever started to feel like a bargain—something traded for your peace—then you’re already close to Tao Yuanming (陶淵明). He lived in a politically unstable age and tried, more than once, to serve from the inside. He took posts, resigned, returned, and tried again—until the same question kept rising: how much of yourself can you give up and still call it a life?

Over time, Tao became the icon of the yǐnshì (隱士) in Chinese cultural memory. Not because every later literatus actually withdrew (many stayed in office), but because Tao offered a lasting alternative: a countryside life as an inner refuge—something like an ideal retirement you could long for when the world grew too loud.

Chrysanthemums appear throughout his poetry, and they came to symbolize that refuge—late-blooming, wind-proof, quietly resolute. In the literati imagination, Tao and the chrysanthemum became paired icons of the same stance: stepping back from noise without losing yourself.

From this point on, the chrysanthemum becomes more than a flower. It becomes a stance.

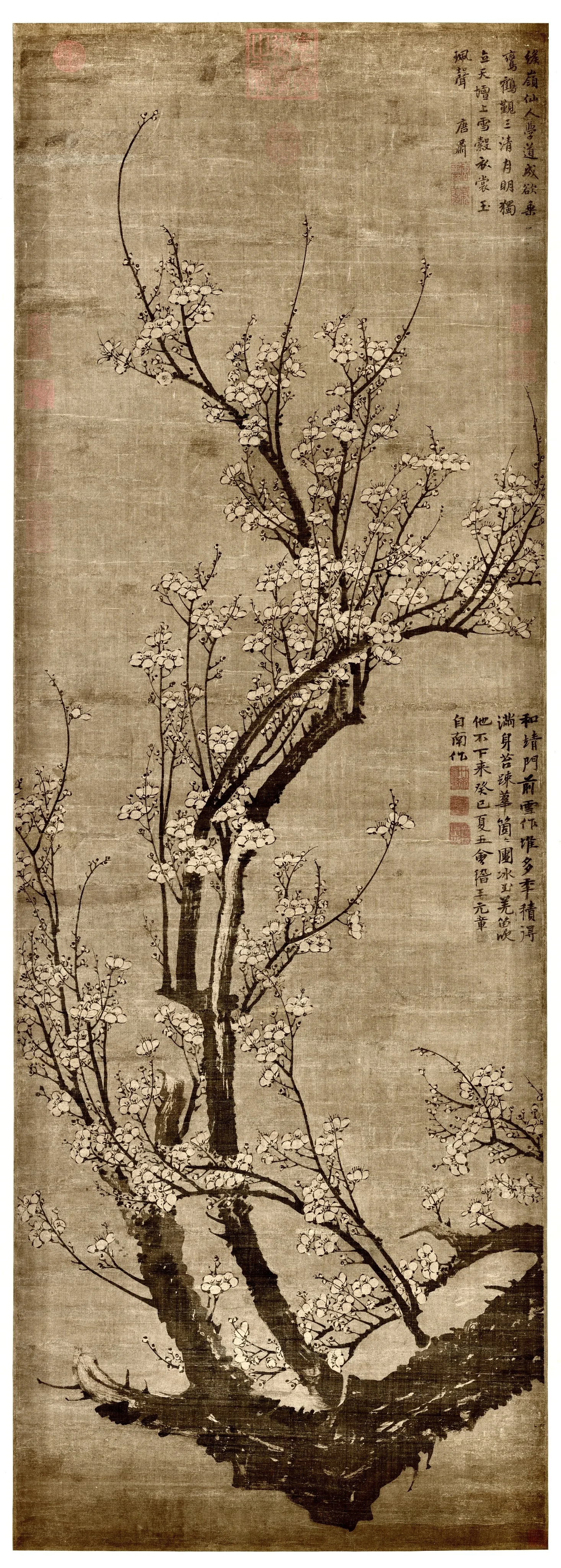

Where “Late Fragrance” Becomes a Painting

After Tao Yuanming, the chrysanthemum gradually entered the visual language of literati painting. Its earliest fully formed expressions appear during the Yuan dynasty. Many scholars of this period lived on the margins of political power, and their art reflects this inward turn.

A key example is Ke Jiusi’s (柯九思) Late Fragrance, Noble Integrity. The composition is spare, the brushwork restrained. The chrysanthemum stands alone, neither dramatic nor decorative.

Chrysanthemums in a Calligrapher’s Hand

The Ming dynasty marks a turning point. As calligraphy—especially cursive script—grew more expressive, painting began to absorb the energy of writing. Chrysanthemums no longer needed to “look like” chrysanthemums; they needed to move like ink.

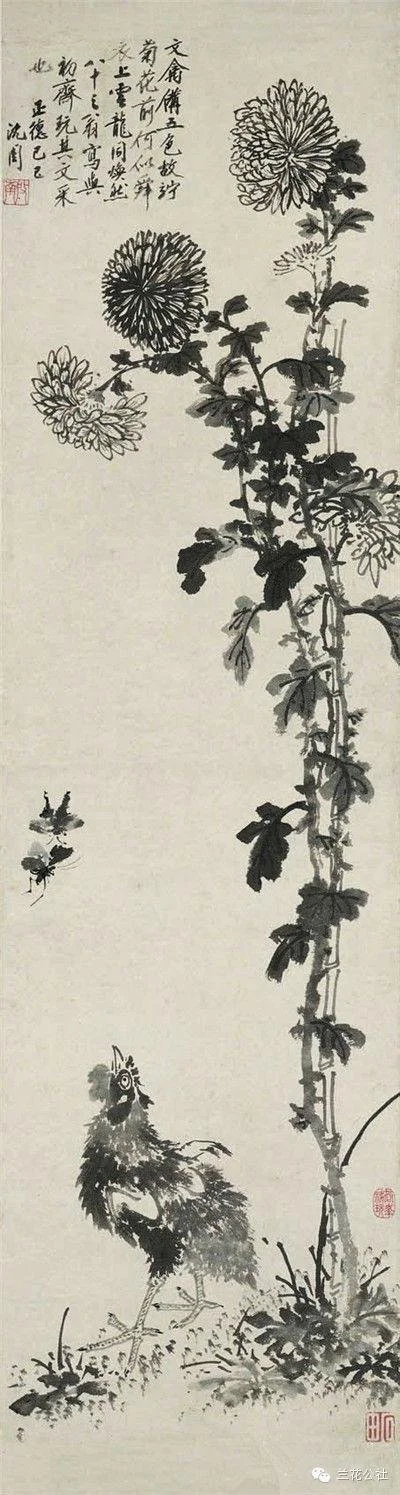

Shen Zhou (沈周) set the foundation for Ming literati chrysanthemum painting in Chrysanthemum and Birds—clear structure, spacious breathing room, and a rhythm that matters more than likeness. His flowers feel contemplative, as if meant to be read slowly rather than admired quickly.

Xu Wei (徐渭) pushed the brush toward raw emotion. In works like Chrysanthemum and Bamboo, the lines edge toward wild cursive, forms fracture, and energy takes over—no longer calm, but unmistakably alive, a mind refusing to collapse under its own intensity.

This chrysanthemum is no longer calm, yet it feels unmistakably honest— a record of a mind refusing to collapse under its own intensity.

Where Painting Becomes a State of Mind

By the Qing dynasty, expressive ink painting continued—but the gaze turned inward. Chrysanthemum and bamboo became less like symbols to display, and more like ways to register a state of being.

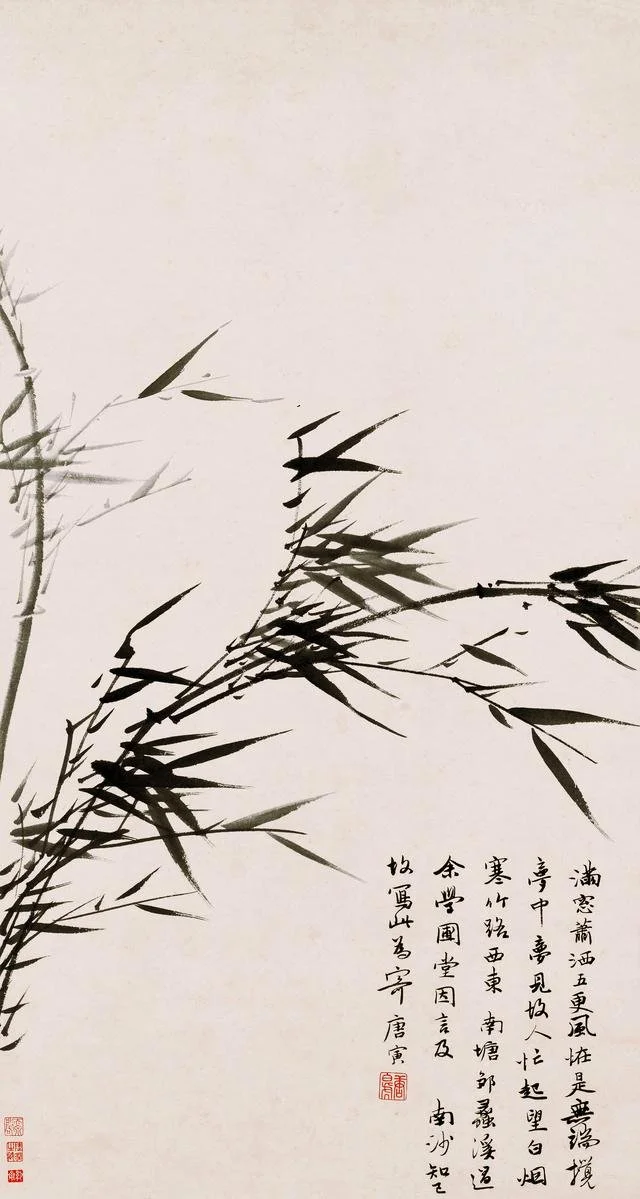

Shitao (石濤) treated nature as a form of self-writing: in his bamboo screen paintings, movement, rhythm, and pause feel like consciousness on paper—an inner landscape rendered through brush and ink.

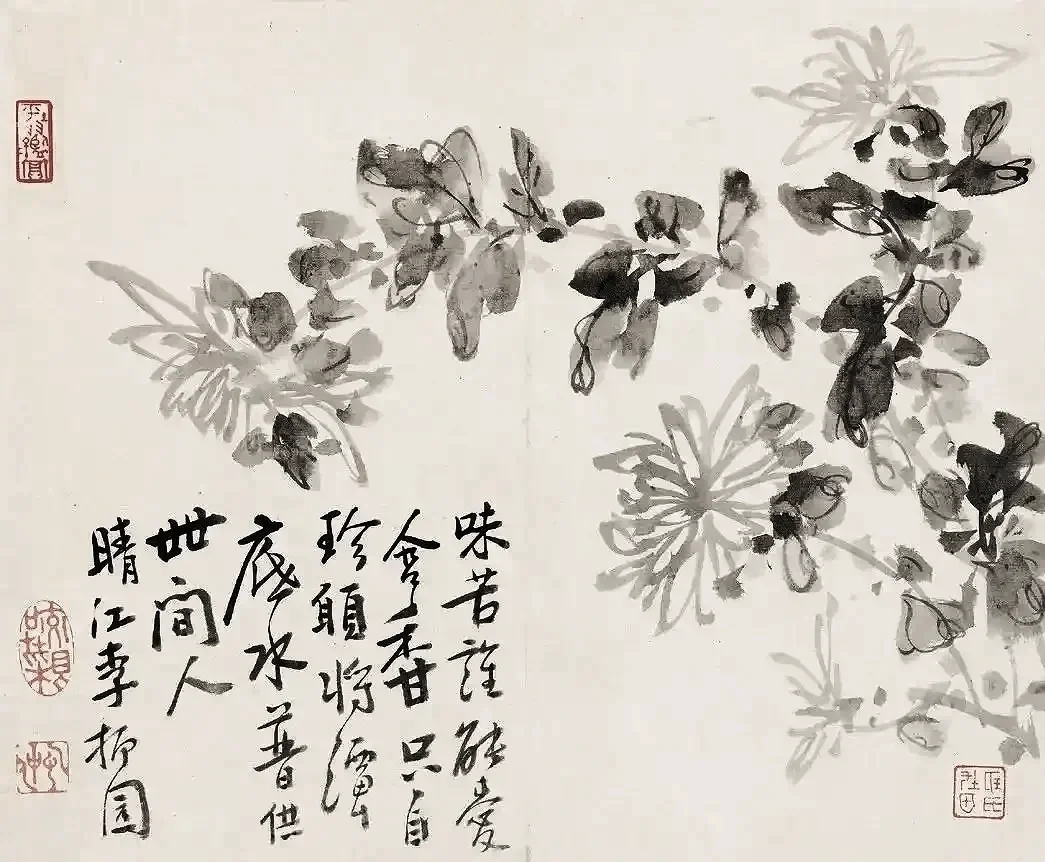

Li Fangying (李方膺) distilled the chrysanthemum into late integrity. His ink chrysanthemums are spare and angular, strong through restraint—standing firm against autumn winds, preserving character at the end of a long road.

From Yuan restraint, to Ming expressive force, to Qing introspective return, the ink chrysanthemum evolves alongside human experience, reappearing whenever the question shifts from achievement to meaning.

Ink Chrysanthemum and Bamboo Painting by Shitao - Twelve Continuous Screens from the Qing Dynasty

The Four Gentlemen, Four Ways to Stay Whole

In Chinese literati painting, plum, orchid, bamboo, and chrysanthemum are called the Four Gentlemen. They aren’t “pretty motifs.” They’re closer to a private vocabulary—four images scholars returned to when life got difficult, and they needed a way to name what they were trying to become.

Each one holds a different kind of strength:

Plum — Pride (傲) It blooms in snow. Not loud, not delicate—just unwavering. The plum stands for moral courage: staying upright when the world turns hostile.

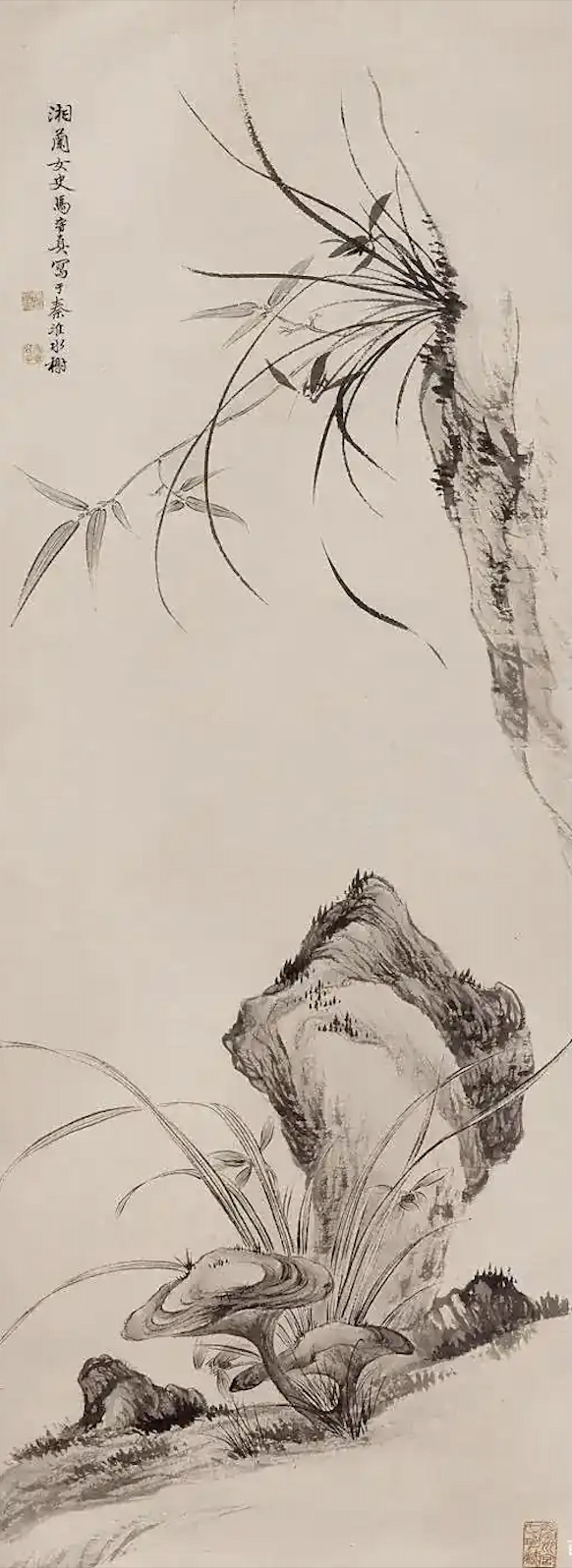

Orchid — Solitude (幽) It grows in hidden valleys and still carries fragrance. The orchid is integrity without applause—the ability to remain refined even when no one is watching.

Bamboo — Restraint (澹) Hollow inside, upright outside. Bamboo is adaptability with backbone: bending with reality while keeping your inner line.

Chrysanthemum — Reclusion (逸) It blooms late, when everything else is done. The chrysanthemum carries an unforced ease, a graceful step back from noise without losing yourself. It’s the flower that appears when ambition softens into clarity.

Plum, orchid, and bamboo teach you how to endure. The chrysanthemum asks the quieter, later question: After the struggle—how do you rest, and still remain yourself?

How to Read the Ink Chrysanthemum

The next time you see an ink chrysanthemum—on a scroll, in a book, behind glass— try asking not “Is it beautiful?” but something quieter:

Does the flower feel tense, or quietly sure of its place?

Do the strokes feel like they’re exploding outward, or gathered and steady?

When you step back, does the painting feel loose and leaking, or calm and contained?

Very often, these questions tell you more than “Does it look like a chrysanthemum?” They lead you toward the painter’s inner weather—and, sometimes, toward your own.

Extend this way of seeing into life

The Four Gentlemen were never just plants. They were portraits of how to live with dignity, even when no one’s watching.

Bamboo taught how to bend without breaking.

Orchid, how to stay true in solitude.

Plum, how to bloom through frost.

And chrysanthemum—always the last to arrive—taught us how to let go with grace.

In a world that keeps asking us to move faster, these paintings offer a gentler art:

To know when you’ve done enough.

To step back without disappearing.

To finish—without losing yourself.

And still remain whole.