Ink Plum Depicting the Art of Endurance

How the Chinese literati turned winter’s solitude into a study of strength and awakening.

In the snow of winter, when all else fades into silence, the plum blossoms. Its fragrance rises not in abundance, but in defiance. To paint a plum is to paint the quiet strength that survives the cold— the courage to bloom when nothing else dares.

Among the “Four Gentlemen,” the plum stands for renewal and endurance— a eulogy to life reborn through hardship. It blossoms amid snow and desolation, singing of beauty that emerges from perseverance, and of spring’s return promised through frost. For centuries, painters have sought not to record its image, but to embody this spirit of endurance through brush and ink. And within this practice lives the ancient idea of Xi Shen— to paint not what you see, but what you feel when life reveals its quiet strength.

Xi Shen(喜神) — Rendering the Felt Essence

In the Southern Song, the painter Song Boren (宋伯仁) compiled The Manual of the Spirit of Plum Blossoms (Meihua Xi Shen Pu). Here, the word xi (喜) means more than “to love.” It is to capture, to echo, to respond—the act of seizing what moves you. And shen (神) is more than “spirit”: it is the inner vibration of things—their feeling, gesture, attitude, and expression.

Thus Xi Shen is not imitation, but translation of experience. When you face a plum in snow, you do not copy its petals; you paint what you felt in that meeting—the endurance, the clarity, the quiet joy of survival.

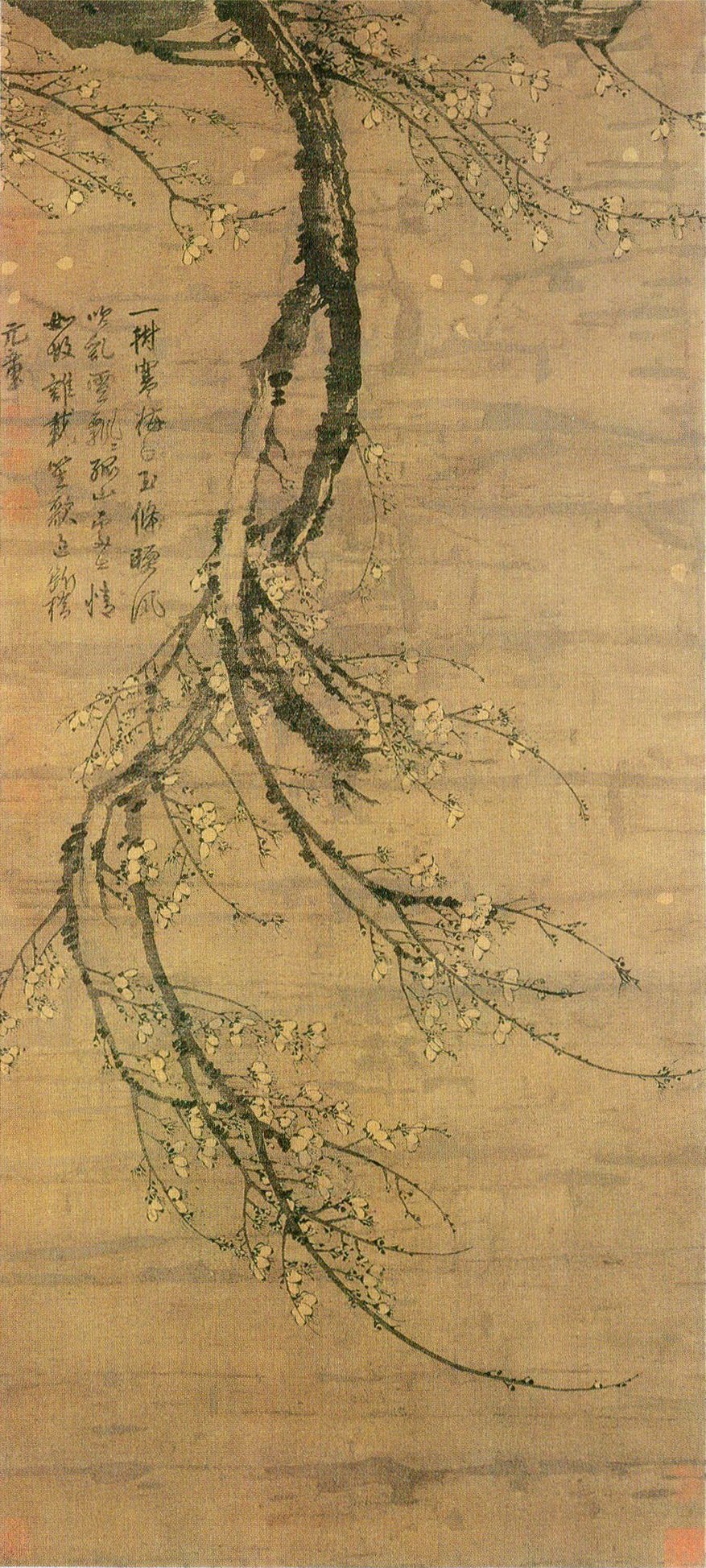

To see this idea beautifully embodied, one can look to the work of Guan Daosheng (管道昇), the renowned female painter of the late Song and early Yuan. Though best known for her bamboo, her plums reveal a quiet decisiveness beneath delicate brushwork. Each branch moves with intention, each bud holds its breath, as if painted from the inner rhythm of the scene rather than its outward form. In her hands, Xi Shen becomes visible: not bold display, but the subtle pulse of what the heart has truly encountered.

The Story of Wang Mian (王冕)— The Plum’s First Heart

Where Guan Daosheng embodied the quiet, inward pulse of Xi Shen, Wang Mian (王冕) carried this same principle into a clearer, more resolute expression. For him, the plum was not merely a presence to be felt—it was a calling. Born poor in the Yuan dynasty, he tended temple lamps as a boy and secretly copied a wall painting of plum blossoms until fascination turned into devotion. When grown, he painted only in ink—his plums, his own voice. Asked why he never painted peaches or pears, he smiled:

“Amid forests of ice and snow, the plum stands apart,

unlike the peach and pear that mingle with the dust of spring.

Then, in a single night, its hidden fragrance stirs—

unfurling a sweep of spring across the vastness of the world.”

In his poem Ink Plum, he wrote:

“By my ink-washing pool it grows, each bloom a trace of pale ink.”

This was not description but conviction—ink as the scent of snow, brush as the discipline of heart. Wang Mian’s plum became the emblem of literati virtue: pure, humble, self-sustained. Through him, the plum ceased to be a flower and became a moral stance—a soul that blossoms through endurance.

From Representation to Resonance — The Abstract Journey of the Ink Plum

From the Song to the Yuan, artists shifted from seeing form to sensing breath. After Wang Mian, the Ming dynasty further refined the literati plum through painters such as Chen Hongshou (陳洪綬). His plums are clear, sparse, and rhythmically poised—branches that seem to think before they move. In Chen Hongshou’s hands, the plum became even more introspective, more attuned to silence and space, extending the lineage of “ink as temperament” established in the Yuan.

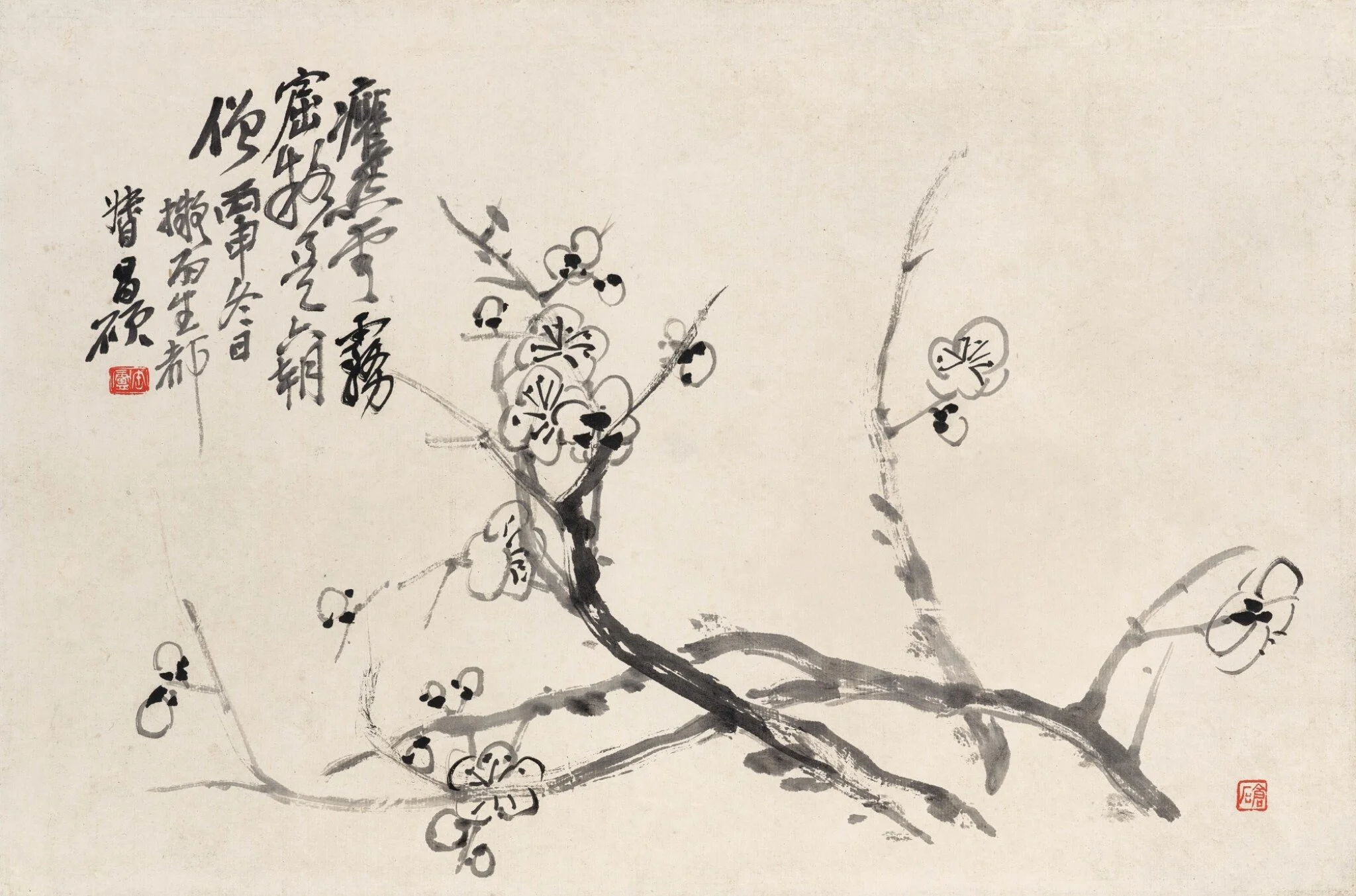

By the Qing dynasty, this sensibility deepened into full abstraction, carried by masters whose plum blossoms were no longer depictions, but states of mind.

Shitao (石濤) declared, “Brush and ink must follow the age,” turning painting into a living philosophy.

Bada Shanren (八大山人) reduced the world to a few strokes—the silence of exile distilled into pure gesture.

Wu Changshuo (吳昌碩), later, wove seal script and painting together, making trunk into written line, flower into rhythm, so that his plums seemed both carved and sung.

Through these hands, the plum evolved from symbol to pulse—from resonance to revelation. When the cadence of calligraphy entered painting, the brush no longer copied the visible— it resonated with the invisible. This is the essence of Chinese art: to paint not objects, but the breath between them.

How to Read the Ink Plum

When you next encounter an ink plum painting, try looking through the lens of Xi Shen: to capture, to echo, to respond— to sense the moment where the painting meets your inner movement.

Look for:

• The Gesture of the Stroke — Observe how the branch turns, bends, or reaches.

Ask yourself: What attitude is this line expressing? Calmness? Resilience? Defiance?

• The Breath in the Ink — Where the ink thickens or fades, there may be wind, cold, or lingering fragrance.

Let the transitions of ink guide your emotional reading.

• The Silence of the Empty Space — Blank space is never empty—it often holds the cold air, the distance, the scent.

Feel what is suggested rather than drawn.

• The Emotion the Plum Awakens — A good ink plum doesn’t show you a flower; it lets you sense endurance, clarity, rebirth.

Let yourself pause and ask: What part of me is this painting touching?

Extend this way of seeing into life

Just like reading a plum painting, you may look at people, places, and moments with the same attentiveness:

• Capture what moves you — A gesture, a sentence, a glance, a breeze.

• Echo its rhythm — Understand not only what you see, but what you feel beneath it.

• Respond with your own presence — Let what touches you become a spark of expression—in painting, in writing, in daily living.

In this sense, reading a plum is also reading life: the art of being moved, and transforming that movement into beauty. If this resonates with you and you’d like to explore ink painting further, feel free to reach out through the form below.